Figure 1: Extract from typical SEC Inline XBRL report

Figure 1: Extract from typical SEC Inline XBRL reportIn 2023, Inline XBRL text block tagging became mandatory for European Single Electronic Filing (ESEF) reports. Unlike previous Inline XBRL reporting systems such as UK Companies House and US SEC reporting, ESEF reports often make use of heavily-styled XHTML designed to replicate the layout and appearance typically seen in PDF financial reports.

The ability of Inline XBRL to provide a single document that combines both human-readable content and machine-readable data into a single document, without compromising on the appearance of the report is very powerful and opens the door to the adoption of Inline XBRL in a wider range of reporting systems.

The use of heavily-styled XHTML creates some specific technical issues for text block facts. The extent to which the rendering of the XHTML fragment contained in the value of a text block fact extracted from an Inline XBRL report should replicate the appearance of the same content appearing in the Inline XBRL has been a source of concern for preparers and reviewers alike.

This working group note discusses the technical challenges with Inline XBRL text block tags, and makes a number of recommendations on how to address them.

This Working Group Note describes the current position of the XBRL International Base Specification Working Group and is published for the purpose of documenting the issues currently encountered with text block tagging, and collecting feedback on the proposed solutions.

All stakeholders are requested to provide feedback to spec@xbrl.org within six weeks of the publication date of this document. If you wish to provide feedback, but are unable to meet this timescale, please communicate your intention to provide feedback within this period.

Software developers are encouraged to prototype and test the proposals made in this document, but the approaches described are not ready for production use. As described in Section 6, additional specification and guidance development is required to fully define the proposed solution.

Block tagging (or "text block tagging") refers to the practice of tagging sections of text content in an XBRL or Inline XBRL report. Block tags can be used to tag single sentences, paragraphs, or even full reports, including images, tables and any other content.

XBRL taxonomy concepts used for block tags usually have a data

type of textBlockItemType (as defined in the DTR), and the content of

a block tag is a fragment of XHTML, meaning that the content can contain

formatting instructions.

This document discusses the issues currently seen when applying block tags to ESEF reports. This can be categorised into two broad categories:

These are discussed separately.

The Inline XBRL specification provides a mechanism (the escape="true"

setting) for tagging part of an Inline XBRL report such that value of the

extracted XBRL fact is an XHTML fragment containing the contents of the Inline

XBRL tag.

Although the Inline XBRL specification defines how these XHTML fragments are obtained from the source document, it does not say anything about how these extracted XHTML fragments are to be used or displayed, and this lack of specification is at the heart of many of the display issues seen with block tags.

There are many potential issues that can occur when extracting a fragment of XHTML from a larger document and attempting to display it. For example:

The fragment may use CSS classes for styling. These rely on a separate stylesheet that does not form part of the extracted fragment, meaning that the resultant rendering may look quite different to the original.

Even if the fragment uses inline CSS styling, the styling may rely on the styling of enclosing XHTML elements that do not form part of the fragment.

As a simple example, the text may use a white font colour because it is displayed on a dark background, but the element with the dark background is not included in the fragment. If the extracted XHTML fragment is then displayed against a white background, the text will be unreadable.

Another example is an XHTML element that uses CSS positioning to position the element relative to some ancestor. If that ancestor is not included in the fragment, it is unlikely to display correctly.

The fragment may include images using relative URIs. There is no guarantee that images will be available at the same URIs if the fragment is displayed.

Prior to the introduction of block tagging as part of the European Single Electronic Filing (ESEF) programme, the most notable use of block tags has been in filings to the US SEC. The use of block tags at the SEC has been successful as the potential issues with displaying extracted fragments of XHTML discussed above are not a problem in practice. There are a number of reasons for this:

SEC filing rules mandate the use of inline CSS styles. This removes the issue of CSS class definitions being unavailable when displaying the text block. The use of inline CSS styles is prescribed by the Edgar Filer Manual, and enforced by validation.

The styling applied to Inline XBRL documents filed to the SEC is typically quite simple, and does not make use of CSS positioning to achieve complex document layouts, custom fonts, or heavily-styled table backgrounds and borders.

The SEC provides viewer software that provides a de-facto specification of how text block content is to be displayed.

The software is freely available, allowing preparers (and their software providers) to ensure that block tags display correctly in this software.

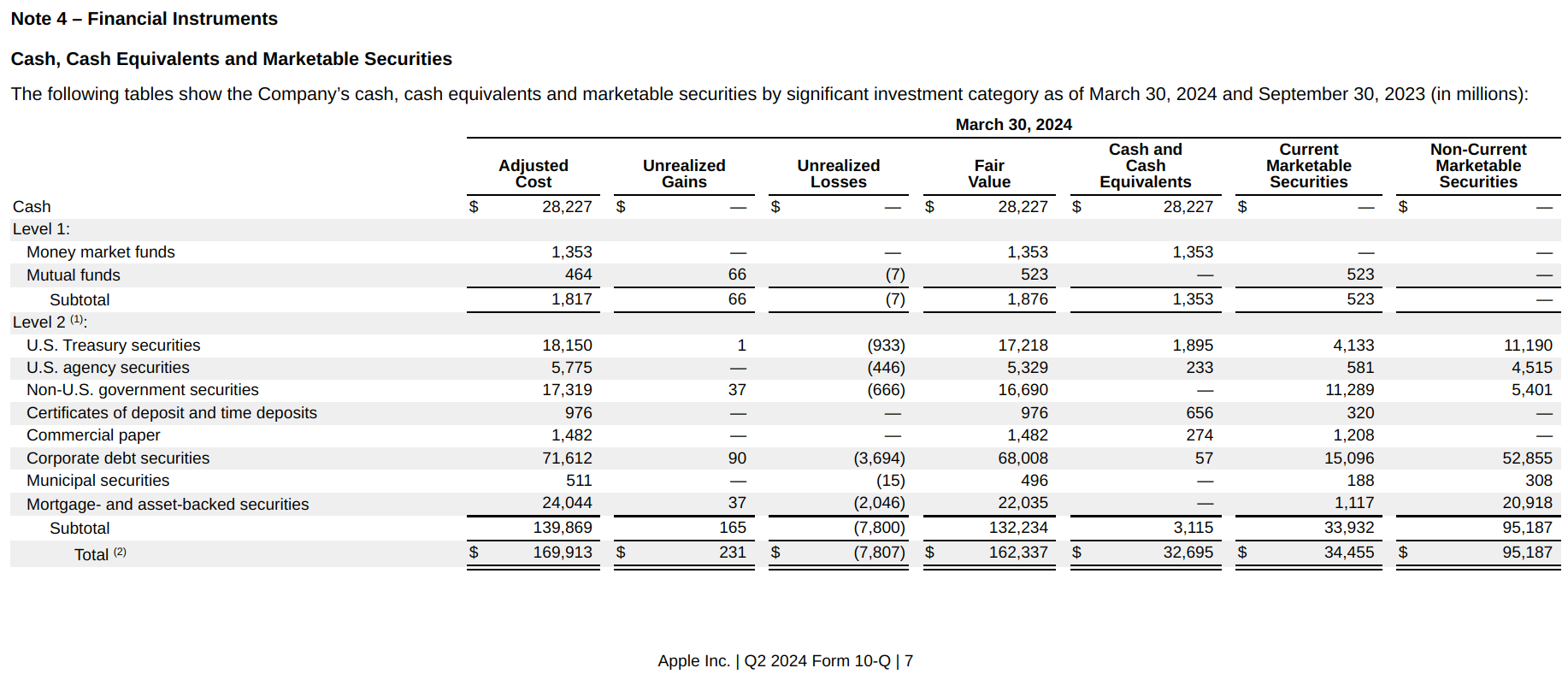

An extract from a typical SEC Inline XBRL report is shown in Figure 1.

An example of a text block tag shown in the SEC's viewer is shown in Figure 2.

The ESEF programme (and the closely related UK-equivalent, UKSEF2) has many similarities with the SEC's, but the nature of the XHTML in ESEF Inline XBRL reports is often very different to that of SEC filings. ESEF reports commonly make use of heavily-styled XHTML designed to replicate the layout and appearance typically seen in PDF financial statements.

An example of a page from a typical ESEF report is shown in Figure 3.

Common features of such reports include:

A fixed layout that does not respond to the size of the display window.

A paginated layout, replicating the distinct pages common in a PDF report.

Fixed text layout. Individual lines within a paragraph are absolutely positioned, and words do not re-flow onto different lines if the window is resized.

Use of custom fonts, and varying text sizes and colours.

Heavy use of images, including background images that provide page formatting such as table lines and borders.

ESEF filings are not restricted to using inline styles. It would be impractical to achieve the appearance of these documents with such a restriction.

These features can create issues when attempting to display an XHTML fragment. An extreme example of this is shown below.

Figure 4 shows the first part of a text block tag taken from an ESEF report.

Figure 5 shows an isolated rendering of the same block tag. As can be seen, the result is unusable. This is due to inline CSS styles that make use of absolute positioning that relies on container elements that are not included in the text block tag; rather than being positioned relative to separate page containers, they are all positioned relative to the same container, resulting in overlapping text.

Many ESEF reports are currently prepared by converting PDF reports into XHTML, and then add Inline XBRL tags. The PDF conversion process attempts to exactly replicate the appearance of a PDF, and this approach invariably results in the fixed layout features noted above. It also tends to produce very large XHTML documents, as many additional XHTML tags are included in order to precisely position individual lines, words, or even letters.

There is a growing market of XHTML-native report preparation systems that target the creation of XHTML directly. These can often achieve the same high level of design fidelity but with much simpler and cleaner XHTML. Display of block tags drawn from such documents is usually much better than with PDF-converted documents, but is seldom perfect.

It is important to recognise that the use of PDF-conversion preparation solutions has been essential to the success of ESEF. If preparers had not been able to straightforwardly replicate the appearance of their existing PDF reports, it is very unlikely that ESEF's Inline XBRL reports would have been accepted in place of PDF.

It should be noted that the differences described above reflect differences in the underlying reporting requirements. The use of relatively plainly-styled HTML in SEC submissions pre-dates the adoption of XBRL. Similarly, the use of heavily-styled "glossy" annual financial reports has been the norm in many parts of Europe prior to ESEF.

There are also many Inline XBRL reporting systems that do not make of use text block tagging at all.

Inline XBRL is also increasingly used for Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) reporting. ESG reports typically make heavy use of narrative disclosures that are captured in XBRL as text block tags.

A major strength of Inline XBRL is the ability to support, rather than disrupt, existing human-readable reporting practice and combine it with structured, machine-readable data. In evaluating the applicability of the recommendations of this Working Group Note to a given reporting environment, it is important to fully understand the underlying reporting requirements.

Addressing the display issues seen with block tags in ESEF reports requires a new approach. In order to define this approach, we should first consider what block tags are useful for.

It is often assumed that the primary purpose of block tags is isolated rendering — displaying the tag content separately from the source document — but this assumption should be verified.

The use of block tags in SEC filings pre-dates the adoption of Inline XBRL. With an xBRL-XML (XBRL v2.1) report, being able to display the contents of a block tag is critical, as it is the only way to see the content of textual disclosures.

With Inline XBRL, tags are linked to the source XHTML document. Block tags can be used to navigate to, and highlight, the relevant content in the source document, preserving all original styling. Figure 6 demonstrates how the labels in an XBRL taxonomy can be used to search and navigate an Inline XBRL report. In this example, English language labels are used to search a French language report.

Figure 7 shows how Inline XBRL tags can be used to focus on relevant content in a report.

The ability to view block tags in the context of the source document provided by Inline XBRL greatly reduces the importance of an isolated rendering that exactly replicates the appearance of the source document.

Isolated rendering of block tags may actually be more useful if the source styling is removed. As an example, consider an analyst wanting to compare facts for the same concept reported by different companies by displaying them side-by-side.

Figure 8 and Figure 9 show facts highlighted in two different ESEF reports. In both cases, the block tag spans multiple pages, and in the first case, the report uses a landscape layout with multiple columns.

Both examples use a fixed layout; the CSS does not allow the content to be re-flowed to a different line length.

In this case, the source styling hinders a side-by-side comparison of the reports as an unreadably small font size is required if the layout is retained (Figure 10).

It is not possible to render this content, with its styles, outside of the context of the enclosing page, as each line of text uses absolute positioning relative to the enclosing page container.

If instead we remove the source styling, the content can be re-flowed and re-styled to achieve a much more useable result:

Achieving this result requires that the documents contain appropriate structural XHTML tags (see Section 5.1.1).1

Block tags in Inline XBRL reports should support the following use cases:

Disclosure indicator. The presence of a block tag serves as an indicator

that a report contains a fact for that concept. This allows consumers to

quickly find reports containing a given disclosure. This use case would be

satisfied even if the block tags are not connected with the XHTML at all, for

example, by including them as hidden tags, but this approach is neither

proposed nor recommended.

Extraction of structured text. Block tags should allow a user to reliably extract text that preserves just text structure (headings, paragraphs, lists, and tables), and which can be styled and re-flowed by the consumer. This facilitates usage such as the side-by-side view comparison described in Section 3.5.1.

In some cases, there may be little value in supporting the extraction of structured text. This is discussed in Section 4.2.

Block tags in Inline XBRL reports should not attempt to support the isolated rendering of an extracted fragment of XHTML in a manner that retains all source styling and layout.

As noted above, the need for an isolated rendering of block tags is largely redundant with Inline XBRL due to the availability of the tagged source document. Use cases that might otherwise require this are adequately (or better) served by navigation and highlighting, or by the extraction of structured text.

As discussed in Section 3.3, there are significant technical challenges with achieving an isolated rendering of a fragment of XHTML taken from a heavily-styled XHTML document. Indeed, there are significant challenges in even specifying what this would mean. For example, where a block tag is split across multiple pages and columns, is it necessary to maintain the relative positioning of the components of the tag in the isolated rendering?

ESEF filing requirements prescribe a large number of block tag concepts that must be tagged if they are present in the notes to the financial statements in a report. Many of these mandatory concepts overlap, with more specific concepts included that form part of larger, less-specific concepts. The net result of this is that some parts of the report may be tagged many times using nested block tags.

Figure 12 shows an example of a section of a report that has been included as part of 13 different block tags.

The content of some block tag concepts is very large, often including many pages from the report.

The combination of nested tagging, tags that include large parts of the source report, and the inefficient XHTML seen in PDF-converted reports (see Section 3.3.1) can lead to extremely large XBRL reports when extracting data from the Inline XBRL.

There are different views on the benefits of heavily nested tagging. On the one hand, tagging content with all applicable concepts makes it easy for consumers to directly access the content for a given concept. On the other hand, nested tagging increases preparer burden and increases extracted report size, and in many cases consumers can infer a larger enclosing tag from its individually tagged components.

As noted above, some block tags cover large sections of the report. The Working Group considers that these large section-level tags are only useful for the disclosure indicator and navigation and highlighting use cases described in Section 3.6; the utility of extracting structured text from such section-level tags is limited or non-existent, given that all of the content will typically also be tagged by more granular block tags.

This note proposes two approaches for addressing the issues described above:

These solutions are outlined below.

As described in Section 3.6, when extracting content from a block tag,

the goal should be to preserve text structure, but not styling. In order to

facilitate this, it is proposed that new Inline XBRL transformations are

introduced that remove styling information and purely presentational XHTML elements

(<div> and <span>), and leave only unstyled, structural XHTML elements

(see Section 5.1.1).

Consumers already have the ability to strip non-structural XHTML elements and styling today, but as this process is not defined or standardised, report preparers cannot reasonably target this output when reviewing the output of block tags. Many reports do not have the necessary structural XHTML elements for this process to be effective.

By introducing a standardised transformation, preparers will have a clear specification of how block tags will be handled, and can therefore focus on ensuring that block tags produce correctly structured structural XHTML, and avoid expending effort on the effect of styling instructions once they are removed from the context of the surrounding document.

Further, specifying this HTML simplification process as a transformation should

significantly reduce the size of the extracted fact values, as the

presentational <div> and <span> elements are removed as part of the extraction.

The XHTML tags that control the appearance of an Inline XBRL report can be

created in different ways. It is possible to use structural XHTML tags, such as

<p> (paragraph), <h1> (level 1 heading) and <table> (table) that provide

information about the structure of the document.

Alternatively, presentational tags (<div> and <span>) may be used. The

application of CSS styling can be used to recreate exactly the same visual

appearance under either approach, but the information available to consumers

about the structure of the document is different.

The XHTML specification refers to structural tags as "semantic tags" (see section 3.2.1 of the XHTML standard), but this document uses the term "structural" in order to avoid confusion with the semantics provided by Inline XBRL tags.

Although the Inline XBRL specification does not require the use of structural XHTML tags, there are good reasons to prefer structural XHTML tags, where possible. For example, structural XHTML tags improve the accessibility of a report, and can make it easier to navigate. XHTML table tags can be used to capture the row/column structure of a table, making it easier to copy tabular data to other formats (e.g. Excel spreadsheets).

XHTML tagging, even with structural XHTML tags, is not a substitute for Inline XBRL tagging of individual facts. XHTML semantics relate to the structure of the document; Inline XBRL tagging provides additional semantics about the facts being reported such as units, period, precision, dimensions and scaling, and most importantly, connections to a taxonomy that provides the semantic definition of the concepts and dimensions.

This is particularly important for tables, where detailed tagging of numerical data is considered to be the most useful and will provide detailed information about each number being disclosed, whereas XHTML semantics only convey the row and column structure.

Many ESEF documents do not currently contain the necessary structural XHTML

elements required under this approach. These would need to be added as part of

the document preparation process. Some preparation software already provides

the ability to do this with tables (inserting <table>, <tr> and <td> tags

into tables that are laid out using absolutely positioned <div> and <span>

elements). It should be possible for structural XHTML elements to co-exist with

the presentational XHTML that the documents currently rely on. For example,

reports may be able to use the display: contents CSS instruction on structural

XHTML elements to remove any impact on the source document's appearance.

The proposed transform could also provide a mechanism for improving the XHTML

structural information. For example, where a report uses a fixed layout with

<div> elements for pages and columns, a paragraph that spans a column or page

break cannot be marked up with a single <p> tag.

For example, the following is invalid HTML, because the <p> tag is not nested

correctly within a single parent:

<div class="page">

<p>

This paragraph starts on the first page...

</div>

<div class="page">

... and continues on the next page.

</p>

</div>

This would need to be structured as follows, using separate <p> tags:

<div class="page">

<p>

This paragraph starts on the first page...

</p>

</div>

<div class="page">

<p>

... and continues on the next page.

</p>

</div>

This leads to an unwanted paragraph break between the two parts of the

paragraph. The transform could provide a mechanism for constructing a single

<p> tag as part of the block tag extraction process. The details of this

mechanism would need to be defined, but it could, for example, use CSS classes

to indicate that a paragraph follows on from the previous paragraph.

As described in Section 4.2, large, section-level block tags are most valuable for the disclosure indicator and navigation and highlighting use cases. Therefore, it is proposed that an approach for tagging such block tags in a way that produces no extracted content is standardised.

This approach would retain support for the two use cases mentioned above, but would avoid bloating the extracted XBRL report with very large block tag content.

There are existing transformation rules that could be used for this purpose.

For example, ixt:fixed-empty and ixt:fixed-true transform any input content

to an empty string, or the string true, respectively, but it may make sense

to introduce a transform specifically for this purpose.

The choice of which approach should be used for a given tag would need to be prescribed by the relevant filing authority.

The implementation of these proposals (see Section 6) should provide an explicit mechanism, such as standardised datatypes, for indicating which approach is to be used for each concept.

Both of the approaches described above would reduce the extracted report size, and should reduce preparer burden by simplifying, or removing, the content of extracted block tags. As such, these go some way to addressing the issues with heavily nested multi-tagging with block tags. This working group note does not take a position on whether the number of nested block tags required in ESEF reports should also be reduced.

This document aims to describe and explain the issues currently seen with block tags in some Inline XBRL reports, and provides a high-level description of potential solutions.

Adoption of these proposed solutions would require a more formal definition in the form of additional transformation rules and additional datatypes.

The definition of exactly which XHTML tags are included in the extracted output will be prescribed as part of the definition of the transformation rules.

The formal definition of transformation rules and additional datatypes will be accompanied by best practice guidance documenting their use.

Once these components have been defined, updates to filing rules specifying their use will be required.

Many ESEF reports are currently prepared using a process that converts a PDF

document to XHTML. Such a conversion process will not automatically produce

semantic XHTML tags, but will instead produce positioned <div> and <span>

elements that recreate the appearance of the original PDF document.

In such systems, additional effort may be required in order to insert structural

XHTML tags. A number of software vendors have indicated willingness to

implement features that would minimise additional effort required by preparers.

A requirement to produce documents that use structural XHTML tags exclusively may impose an unacceptable disruption to existing preparation processes. The approach described in Section 5.1 would allow structural XHTML tags to co-exist with such presentational XHTML, providing the benefits of structural XHTML tags without removing the ability to use presentational XHTML tags to recreate a fixed layout.

| Date | Description |

|---|---|

| Initial public release | |

| Updated to replace remaining references to "semantic XHTML" with "structural XHTML" |

This document and translations of it may be copied and furnished to others, and derivative works that comment on or otherwise explain it or assist in its implementation may be prepared, copied, published and distributed, in whole or in part, without restriction of any kind, provided that the above copyright notice and this paragraph are included on all such copies and derivative works. However, this document itself may not be modified in any way, such as by removing the copyright notice or references to XBRL International or XBRL organizations, except as required to translate it into languages other than English. Members of XBRL International agree to grant certain licenses under the XBRL International Intellectual Property Policy (https://www.xbrl.org/legal).

This document and the information contained herein is provided on an "AS IS" basis and XBRL INTERNATIONAL DISCLAIMS ALL WARRANTIES, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO ANY WARRANTY THAT THE USE OF THE INFORMATION HEREIN WILL NOT INFRINGE ANY RIGHTS OR ANY IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE.

The attention of users of this document is directed to the possibility that compliance with or adoption of XBRL International specifications may require use of an invention covered by patent rights. XBRL International shall not be responsible for identifying patents for which a license may be required by any XBRL International specification, or for conducting legal inquiries into the legal validity or scope of those patents that are brought to its attention. XBRL International specifications are prospective and advisory only. Prospective users are responsible for protecting themselves against liability for infringement of patents. XBRL International takes no position regarding the validity or scope of any intellectual property or other rights that might be claimed to pertain to the implementation or use of the technology described in this document or the extent to which any license under such rights might or might not be available; neither does it represent that it has made any effort to identify any such rights. Members of XBRL International agree to grant certain licenses under the XBRL International Intellectual Property Policy (https://www.xbrl.org/legal).

Some modification of the reports was required to insert additional structural XHTML tags in order to prepare this example, but such tags could be included in the Inline XBRL reports without hindering the appearance of the source documents. ↩

Further references to ESEF in this document should be taken to also include UKSEF. ↩